Jacobite rising

During the 1745 Jacobite rising, the highland army of Prince Charles Edward Stuart penetrated England as far as Derby where a Council of War was held. Although Prince Charles argued passionately and at length in favour of proceeding with the march on London, Murray, of a more cautious frame of mind, was concerned about the vulnerability of their position and urgently counselled a return to Scotland. In the resultant vote, Charles, to his utter fury, was overruled.

The army turned despondently back to Scotland, which had a detrimental effect on its morale, the strong-headed Charles himself decided with bad grace and spent days sulking over it. Leaving a garrison at Carlisle Castle, later to be utterly annihilated, they reached Glasgow on Christmas Day, 1745.

William Duke of Cumberland

The government forces under General Hawley were met in battle on a moor to the south-west of Falkirk on 17th January 1746, where the Jacobites triumphed. The Prince then made his biggest blunder of the campaign, weeks were wasted in a fruitless and futile attempt to besiege Stirling Castle. Charles stubbornly ignored the advice of the more experienced Murray and most of his chiefs, let the army rest and recuperate over the winter.

William, Duke of Cumberland, the second son of King George II, arrived in Scotland on 30 January to take command of the government forces. He decided to wait until the end of the winter, moving his forces to Aberdeen. A force of Hessian troops, under the command of Prince Frederick of Hesse, took up position to the south to cut off any path of retreat for the Jacobites. On 8 April Cumberland resumed his campaign.

On 14 April Cumberland camped his army at Balblair just west of Nairn. Hugh Rose of Kilravock played host to both Charles Edward Stuart and the Duke of Cumberland on 14 and 15 April 1746, before the battle was fought. He later described Charles' manners and deportment as most engaging. The following day, William, Duke of Cumberland called at the castle and when Hugh Rose received him, he commented, "So you had my cousin Charles here yesterday." to which Rose replied, "What am I to do, I am Scots", to which Cumberland replied, "You did perfectly right."

On 16th April, Charles came to the fatal and foolish decision to lead his now ragged and exhausted army to meet Cumberland's highly disciplined and well-provisioned forces at the fateful field of Culloden. The Jacobite army left their base at Inverness and camped 5 miles (8 km) to the east near Drummossie, around 12 miles (19 km) from Nairn. Culloden Moor is a bleak, treeless, desolate and windswept stretch of ground, lying five miles south-east of Inverness. Due to the number of cannon, the government army possessed the open battleground was extremely ill-chosen. The Jacobite army was in very poor condition, exhausted, hungry and mass desertions had occurred within its disheartened ranks, to add to its troubles, poor planning had resulted in its food supplies being left behind at Inverness.

Culloden Moor

Charles Edward Stuart had decided to personally command his forces and took the advice of his adjutant general, Secretary O'Sullivan, who chose to stage a defensive action at Drummossie Moor, a stretch of open moorland enclosed between the walled Culloden enclosures to the North and the walls of Culloden Park to the South.

Lord George Murray "did not like the ground" and with other senior officers pointed out the unsuitability of the rough moorland terrain which was highly advantageous to the Duke of Cumberland with the marshy and uneven ground making the famed Highland charge somewhat more difficult while remaining open to Cumberland's powerful artillery. They had argued for a guerrilla campaign, but Charles Edward Stuart refused to change his mind.

On 15 April, the government forces celebrated the Duke of Cumberland's twenty-fifth birthday by issuing two gallons of brandy to each regiment. Charles envisioned a plan to attack by dead of night, since the same tactics had been deployed with great success at Preston pans. The advance on Cumberland's camp proceeded at dusk. After an exhausting nine-mile trek the desperately hungry Highlanders realised that they could not reach the enemy lines before dawn and returned wearily to Culloden Moor.

Early on 16 April, the Government set off towards the moorland around Culloden and Drummossie at about 5 a.m. The Jacobite pickets first had sight of the Hanoverian advance guard at about 8 a.m., when they were within around 4 miles (6.4 km) of Drummossie. Cumberland was informed that the Jacobite army was forming up for battle about 1 mile (1.6 km) from Culloden House, on Culloden Moor. By around 11 a.m. the two armies were in sight of one another with about 2 miles (3.2 km) of open moorland lying between them. As the Government forces steadily advanced across the moor, the driving rain and sleet blew from the northeast into the faces of the exhausted Jacobite army.

The Duke of Cumberland is said to have addressed his army before the battle "If there is any man who does not wish to fight the highlanders, I beg him in God's name to go. I would rather fight with one thousand resolute men than ten thousand half-hearted." The Highland army, consisting of no more than five thousand men, faced a formidable and well trained government army numbering around nine thousand troops. The battle, which outcome was imminent, commenced at one o'clock in the afternoon when Cumberland's army discharged their cannon on the Jacobite lines.

The Highland Charge

The air was thick with black smoke and the smell of gunpowder filled the nostrils. The ground beneath men's feet shook with each repeated cannon blast, the Highlanders began to fall in their hundreds. Charles was twice narrowly missed and was moved to a hillock at the back of his army for his greater safety. It must have seemed as if even the elements themselves favoured the Hanoverians when a fierce hailstorm began, which blew in the faces of Charles' army, obscuring the sight of the enemy and stinging their faces, creating further handicaps for them.

The Highlanders stood their ground courageously but suicidally against the murderous barrage of Hanoverian cannon fire. Cumberland's guns then began to discharge grapeshot, leaden balls, nails and pieces of old iron. When they could endure no more, the Highlanders charged frenziedly against the enemy, loudly and angrily shouting "Death or life". Waiting until they were within twenty paces, the well-trained government infantry opened fire.

The Highlanders regrouped and mounted a second valiant but hopeless charge. Jacobite casualties were appalling, estimates place the total Jacobite dead as was well over 1,000. Their bodies lay in heaps, which littered the desolate battlefield, many of the clan chiefs were amongst them. Realising that further resistance was pointless, many of the Highland armies fled the field.

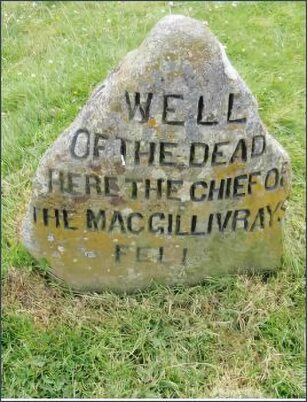

Stone marking the Well of the Dead were the Chief of the McGillivray Clan Fell

Murray brought up the Royal Écossois and Kilmarnock's Footguards, but by the time they had been moved into position, the Jacobite army was in total rout. The Royal Écossois exchanged musket fire with Campbell's 21st and commenced an orderly retreat, but were ambushed by the half battalion of Highland militia commanded by Captain Colin Campbell of Ballimore, who was killed in the encounter. The Royal Écossois and Kilmarnock's Footguards were forced onto the open moor and were attacked by Kerr's 11th Dragoons during which there were further casualties.

The Royal Écossois retired from the field in two wings. One part of the regiment surrendered on the battlefield after sustaining 50 dead or wounded, but their colours were not taken and a large number retired from the field with the Jacobite Lowland regiments. Murray, who had regrouped his men in some sort of order, marched them off with dignity to the sound of bagpipes.

Charles himself had made an unsuccessful attempt to rally what was left of his decimated army, when Sullivan rode up to Captain Shea and commanded Charles' bodyguard: "Yu see all is going to pot. You can be of no great succour, so before a general de route which will soon be, Seize upon the Prince & take him off...". Shea then led Charles Edward Stuart from the field along with Perth's and Glenbuchat's regiments.

Cumberland's cavalry pursued the remainder of the fleeing Jacobites, killing any wounded they came across, no quarter was given. Some of the severely wounded clansmen crawled to a small pool on the battlefield, later ominously termed the Well of the Dead, to drink from its muddied waters. Here they were slaughtered without mercy by the government army. The pool itself became thick with the corpses and ran red with blood.

Butcher Cumberland's soldiers went on to kill indiscriminately any Highlanders they encountered on the route to Inverness, regardless of whether they had been involved in the battle, gender or age. Cumberland himself is said to have pointed at a wounded highlander and ordered Major James Wolfe to shoot him. Wolfe is reputed to have said that his commission was at the disposal of the Duke but not his honour.

The government forces celebrated their victory in rum that evening in Inverness, while as dusk fell on bleak Culloden Moor, an awful spectacle was played out, the smell of death caught up in the merciless wind, while the low moan of the dying mingled in lament chorus with the shrill weeping of women as they roamed the battlefield searching for their menfolk, husbands, fathers, sons and sweethearts, who would now never return home, amongst the multitude of corpses of the dead.

The Battle of Worcester PreviousNext The Battle of Brunanburh