1542-1567. EARLY YEARS

The tragic and tumultuous life of Mary, Queen of Scots began on the stormy night of 7th December 1542. The first Queen of Scotland to rule in her own right was born at the Palace of Linlithgow in West Lothian, the daughter of James V and his French Queen, Marie of Guise.

Her father, James V had experienced a crushing defeat at the hands of the English a few days prior to Mary's birth. A man of a highly emotional nature, this defeat weighed heavily upon him and lead to his death in an abject state of nervous depression. Mary became Queen of Scotland at six days old, becoming Britain's youngest ever monarch. The infant Queen's relative James Stewart, Earl of Arran, was appointed as Regent of the kingdom.

Linlithgow Palace

Mary was crowned at the Chapel Royal, Stirling Castle on 9th September, 1543. She was but nine months old at the time and as yet unable to walk. She was magnificently dressed for the occasion in an elaborate satin jewelled gown beneath a red velvet mantle, trimmed with ermine.

Scotland was at war with England, mirroring the actions of Edward I, three centuries earlier, the overbearing Henry VIII sought to domineer Scottish affairs from London. On the death of his nephew, James V, Henry attempted to gain control of Scotland through proposing that the new Queen of Scots should be married to his only son and heir Edward, later to become Edward VI. The Regent Arran signed a treaty with Henry in 1543, which proposed to unite the thrones of both countries in the young couple.

The Queen Mother, Marie of Guise, supported by Cardinal Beaton, did not favour the alliance and repudiated the agreement. Henry, domineering and savage when crossed, again invaded Scotland, mercilessly burning and ravaging the country in what came to be quaintly termed by the Scots as the 'rough wooing'. For her greater safety. the child Queen of Scots was taken to the island of Inchmahome. After the demise of Henry VIII, the Duke of Somerset, Protector for his young son, marched a further army north and defeated the Scots at the Battle of Pinkie Cleugh on 'Black Saturday', 10th September 1547.

Marie of Guise formed an alliance with her native France through which she hoped to acquire protection. The now six-year-old Mary was betrothed to the young heir to the French throne, the Dauphin Francis. She spent the rest of her childhood at the court of her father-in-law, Henri II. Mary was a pretty child and brought up in the same nursery as her future husband and his siblings became very attached to him. Mary was married to the Dauphin Francois on 24 April 1558 at Notre Dame. She corresponded regularly with Mary of Guise, who remained in Scotland to rule as regent for her daughter.

Mary also possessed a hereditary claim to the throne of England, through her grandmother, Margaret Tudor, eldest daughter of Henry VII. On the accession of Elizabeth I of England, considered by the Catholics to be illegitimate, Mary's father-in-law quartered the arms of England with those of the Queen of Scots, thereby declaring her the true heiress to England. Elizabeth was never to forget this insult and her father-in-law's actions were to have disastrous results for Mary in the future.

For the present, however, Mary was the cosseted darling of the French court, the doting Henri II wrote 'The little Queen of Scots is the most perfect child I have ever seen.' He corresponded frequently with Marie of Guise, expressing his delight in his young daughter-in-law. Mary's maternal grandmother, Antoinette of Guise, in a letter to her daughter in Scotland, stated that she found Mary ' very pretty, graceful and self assured.' On the death of Henri II, Mary's young husband Francois ascended the throne making Mary Queen Consort of France.

The influence of Protestantism grew steadily in Scotland in her absence, urged on by the person of the fiery and fanatical preacher John Knox. The Catholic Mary of Guise fought a losing struggle to contain the inexorable march of the Reformation.

When Marie of Guise died, the young Mary, sharing her father's emotional nature, was distracted with grief at her loss. Her cup of sorrow was not yet full and a few months later her delicate husband Francois II, died from an ear infection making the eighteen-year-old a widow and no longer welcome or influential at the French court, now controlled by her wily mother-in-law, Catherine de Medici.

RETURN TO SCOTLAND

After time spent in mourning for her husband, Mary decided to return to her native land of Scotland, she sought safe passage to England from her cousin Elizabeth I, Elizabeth, still smarting at the insult delivered by Henry III at her accession, refused to grant the favour. Mary sailed to Scotland regardless, arriving at Leith on August 19, 1561, in a thick Scottish mist. Her Protestant bastard half-brother, James Stewart, stepped into the role of her defender, chivalrously guarding her door, sword in hand, against angry protestations from her subjects, when Mary practiced the Catholic mass. The grateful Queen created him Earl of Moray in reward.

Mary was regarded with suspicion by her Protestant subjects. Confrontations with the unyielding and fanatical Knox reduced the emotional and inexperienced Mary to tears. She continued to attend the mass but in acceptance of the situation, tolerantly gave official recognition to the reformed religion. At first, she allowed herself to be lead by wise ministers, but gay and pleasure-loving in the finest Stewart tradition, Mary soon began to exhibit a more willful and impulsive streak. In attempting to govern the rebellious Scots nobility she faced an unenviable challenge.

Mary's character and appearanceThe Queen of Scots was considered a beauty by the standards of her own time, though not perhaps to the modern eye. She had her father's dark auburn hair and aquiline nose along with dark, captivating, slanting eyes in a beguiling heart shaped face and the height and build of her Guise mother. She was described by a contemporary as having "withal an alluring grace, a pretty Scotch accent, and a searching wit clouded with mildness. Fame might move some to relieve her, and glory join with gain might stir others to adventure more for her sake"

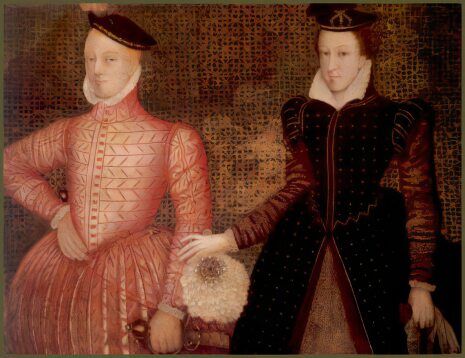

Mary, Queen of Scots with Henry, Lord Darnley

Her appeal seems to have been in her considerable personal charm to the opposite sex. She had inherited her father's tendency to nervous collapse at times of stress.

HENRY STUART, LORD DARNLEY

It was expected that the Queen would soon marry and produce a male heir to Scotland's throne. As a Queen Regnant, she was one of the greatest prizes in the marriage market of Europe. Elizabeth I of England, who wanted influence in the matter of Mary's marriage in return for recognition as heiress to the English throne, offered her favourite, Robert Dudley, rumoured to be her lover. Mary, who perceived this offer as an insult, indignantly refused it.

She considered Don Carlos as a possible husband, the highly inbred and half-witted heir to Elizabeth I's rival, Phillip II of Spain, before deciding on her handsome cousin Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley. Tall, fair-haired and clean-shaven, Darnley, described by a contemporary as 'lady-faced', was the son of Matthew Stewart, Earl of Lennox and Lady Margaret Douglas, herself the daughter of Margaret Tudor by her second marriage to Archibald Douglas, Earl of Angus, therefore himself possessing a claim to the English throne.

Edinburgh Castle

Darnley had been brought up in England and was accordingly regarded as one of Elizabeth's subjects. Mary seems to have been smitten by him and impulsively rushed into marriage at Holyrood on 29th July 1568. On hearing the news, the furious English Queen, who had expressly forbidden their union, venomously imprisoned Darnley's mother, Lady Margaret, in the Tower of London.

Mary's marriage to Henry Stuart proved to be a disastrous one. Arrogant, dissolute, self-seeking and a drunkard who demanded power, Darnley was soon to make Mary repent her impulsive choice. Mary came to regard her foolish husband as an embarrassment and spent much time with her favourite Italian musician, David Rizzio. Rumour swept through the Scottish court that Rizzio was the Queen's lover and driven by jealousy, Darnley burst into the Queen's apartments with Lord Ruthven and others of the Scots lords, clad in armour. Rizzio was stabbed brutally many times, while he tried to cling to the Queen's skirts for protection. Mary was heavily pregnant at the time. She was never to forgive her husband this outrage and grew to regard him with an intense loathing.

In June, 1566, at Edinburgh Castle, a son was born of this tempestuous union, named James Charles. The child was born with a fine caul, like a veil over his face, which was part of the amniotic sac.

Darnley coldly cast aspersions on his son's legitimacy, heightening the Queen's resentment of her husband. Elizabeth I, although reported to be secretly depressed at the news of his birth, stood as godmother by proxy to the Scottish Prince at his baptism.

THE MURDER OF DARNLEY

On the night of 10th February 1566, Darnley, while recuperating from syphilis at a house at Kirk'o Field near Edinburgh, was murdered. In an explosion that shook Edinburgh, the house was blown up with gunpowder and Darnley and a servant was found dead on the grounds. They had been strangled, presumably having escaped the blast. James Hepburn Earl of Bothwell, was considered by many to be responsible for the act and the Queen's complicity in her husband's murder suspected. The skull of Darnley, pitted with the telltale marks of syphilis, is now in the possession of the College of Surgeons at Edinburgh.

Darnley's shocked and grieving father, Matthew Stewart, Earl of Lennox, angrily demanded an inquiry into his son's murder. The Queen duly complied, and Bothwell was declared innocent of any involvement in Darnley's death. There were many, including Lennox himself, who were sceptical of this verdict and saw it as little more than a whitewash.

JAMES HEPBURN EARL OF BOTHWELL

Despite advice urging her to the contrary, the Queen heedlessly and foolishly consented to marry Bothwell. The ill-starred marriage took place according to Protestant rites on May 15, 1566, at Holyrood Palace. The outraged Scottish lords rose in revolt in the name of the now fatherless Prince James. Mary and Bothwell faced the rebels at Carberry Hill, but the ranks of her troops were decimated by desertions and she was forced to negotiate with the lords rather than risk battle. The Queen agreed to surrender to her enemies on the promise that no further action would be taken against her. Bothwell, who as part of the agreement was allowed to leave unharmed, eventually made good his escape to Norway.

On arrival, he was imprisoned in Dragsholm Castle, where he was chained to a pillar half his height, rendering him incapable of standing upright. He was to remain there, crouching in the dark and covered in filth until his death ten years later. His body had become overgrown with hair. Bothwell's mummified corpse was later put on display in the crypt at Faarevejle Church, near Dragsholm.

ABDICATION

Mary was lead captive back to the capital by the lords and abused by the people, dirty and dishevelled and with tears flowing down her face, as their shouts of "burn the whore" rang in her ears, her humiliation was complete and her reputation in tatters. She was later sighted half naked, hysterically weeping and desperately calling for aid at the window of the house where she was held prisoner.

Removed to the island castle of Lochleven, she was bullied and threatened and cajoled into abdicating in favour of her infant son, James. Her treacherous bastard brother James, Earl of Moray, was duly appointed Regent. Undefeated and using her legendary Stewart charm to solicit aid, the Queen managed a daring escape from her island prison. Swiftly gathering together an army, Mary met the rebels in battle at Langside on 13th May 1568. On losing the battle the Queen fled, though advised by friends on the foolishness of such a course, Mary disregarded their pleas and impulsively rode for England to seek protection and support from her 'dear sister and cousin' Elizabeth.

THE YEARS OF ENGLISH CAPTIVITY

On her arrival in England, Queen Elizabeth I refused to grant her cousin an audience, and instead placed Mary in confinement at Carlisle Castle. Lady's Walk, at the castle, is named after her, as it was here that she used to take exercise during her captivity. The Scots Queen was moved to Bolton Castle in July 1568, where she was placed under the care of Henry the 9th Lord Scrope.

Tutbury Castle, Staffordshire

Elizabeth ordered an enquiry into the murder of Darnley, which the Scots lords were invited to present their evidence before. The English Queen was in a dilemma. She could not place her cousin at the head of an army against the Protestant Scots lords, as such would mean political suicide for her. On the other hand, she could not allow her to go to France to solicit aid, such a scenario would place a foreign power at England's back door. Equally, to keep Mary in England was to make her the inevitable focus of Catholic plots.

The chief evidence presented at the enquiry were the so called Casket Letters, a set of eight letters purportedly written by Mary and found in a silver box, said to once belong to Francois II, Mary's first husband. They were accepted as genuine at the time, although doubt now exists as to whether they actually were.

Elizabeth, with characteristic caution, decided not to let the enquiry reach any verdict and decided to retain Mary as a prisoner in England. She was to remain Elizabeth's prisoner for nineteen long and weary years. While she languished in her English prison, Mary's son James, now King of Scotland, raised in the Calvinist religion, was brought up by her enemies to regard his mother as an adulteress and the murderess of his father.

Mary's captivity in England was prolonged and tedious, she was moved between the castles of Sheffield, Tutbury, Wingfield, and Chartley. Mary passed the time at embroidery, a visitor wrote "All the day she wrought with her needle and that the diversity of colours made the time less tedious". The Queen passed many hours at the hobby, in the company of the formidable Bess of Hardwick, her jailer's wife. She drew her inspiration from sources such as emblem books, natural history books, and fables. She also read and wrote letters. She kept several pets including lap dogs and singing birds.

Mary's health began to decline due to lack of exercise and she gained weight. She concentrated her considerable energies on procuring her release by entering into conspiracies against her English cousin. Notes were frequently smuggled into her and Mary's hopes of eventual release were never quite extinguished. Throughout the 18 years of her weary English imprisonment, the Queen of Scots came to symbolise the hopes of the English Catholics.

Tutbury Castle

Mary was moved to Tutbury Castle in Staffordshire on 4th February 1569, its cold and draughts had a detrimental effect on her health and she came to loathe the castle and complained that in winter that the wind would whistle through her chamber. Describing it as "sitting squarely on top of a mountain in the middle of a plain" subjecting her to all the winds and "injures' of heaven".

She was moved from Tutbury in 1569, but returned there in 1570 after the failure of the Norfolk plot and placed under the guardianship of Sir Ralph Sadler, Chancellor of the Duchy of Lancaster. Sadler acted with kindness toward Mary, and allowed her to hawk and ride. He was later replaced by the severe puritan Sir Amyas Paulet, whom Mary came to detest. He humiliated her by removing her royal cloth of state, which reduced the Queen to tears.

Mary's confinement under Paulet became much more severe, she had previously been allowed to walk in the privy garden within the Castle walls, but this was now prevented. The Queen had distributed money to the poor on Maundy Thursday. In 1585, 42 girls and 18 little boys received 1½ yards of woollen cloth. Money was also given to the poor of Tutbury town. Paulet reacted in fury at this and stopped it immediately. Mary was moved on to Chartley Castle in 1585.

After enduring many years of English captivity, Mary attempted to negotiate with James through a Guise emissary for an 'Association', or joint rule with him in Scotland. Her opportunist son, however, was more eager to gain the approval of Elizabeth, to favour his own ends and concluded that the 'The Association desired by his mother should neither be granted or spoken of hereafter.' Mary deeply wounded, wrote 'I am so grievously offended at my heart, at the impiety and ingratitude that my child has been constrained to commit against me.'

The desperate Mary entered into a plot with Elizabeth's maternal cousin, the Catholic Thomas Howard, Duke of Norfolk, one of the most powerful noblemen in England. They plotted to assassinate the Protestant Queen and place Mary on the throne of England with Norfolk as her consort. The plot was uncovered by Elizabeth's agents and Norfolk was sent to the block. Although her life was spared, Elizabeth ensured that Mary's confinement now became more rigorous. As a direct result of the plot, Parliament introduced a bill in 1572 which excluded Mary from the throne. Elizabeth, however, refused to assent to it.

THE TRIAL AND EXECUTION OF MARY QUEEN OF SCOTS

A scheme was devised by Elizabeth's spymaster, Francis Walsingham, designed to end the threat posed by Mary and bring her to the block. In 1586, Anthony Babington, a young and ardent Catholic, played the leading role in a conspiracy to free Mary. Coded messages to and from Mary were sent in beer barrels, the barrels, along with their incriminating replies were regularly intercepted by Walsingham's agents. When Mary responded positively to the plotters, as Walsingham hoped she would, her death knell had sounded and her fate sealed. Walsingham then pounced on the unsuspecting Queen. The plotters were arrested and executed and the Queen put on trial for her offences.

The trial of Mary, Queen of Scots, presided over by 40 lords, took place at Fotheringay Castle in Northamptonshire. Mary represented herself ably, warning her judges " Remember, the theatre of the world is wider than the realm of England." The verdict was a foregone conclusion and she was found guilty. Elizabeth, after much prevacation, due to her fears that her cousin's execution would provide the arch Catholic Phillip of Spain with the excuse he required to launch an invasion of England, was finally prevailed upon to sign Mary's death warrant.

Mary, Queen of Scots passed the night before her execution in distributing her few belongings to the faithful servants who had remained with her in captivity and writing letters to her brother-in-law, the King of France and Phillip II of Spain, requesting that he reward her servants, before lying down on her bed without undressing.

A message was sent to her errant son James, informing him that her dearest wish had always been to see the kingdoms of England and Scotland united. She went to her death in the Great Hall at Fotheringay Castle on 8th February 1587 displaying sublime courage. Every inch a Queen, she walked with resolution and dignity to the scaffold. Dressed all in black satin and velvet, Mary wore a deep red petticoat, the colour of martyrdom.

Mary, Queen of Scots

On the scaffold, ignoring the Protestant Dean of Peterborough who prayed vociferously and at length in English, the Queen of Scots prayed aloud in Latin. When the executioner, following established tradition, asked the Queen's forgiveness, she replied " I forgive you with all my heart, for now, I hope you will make an end of all my troubles."

Having undressed to her underwear and been blindfolded by her attendants, the Queen crossed herself and laid her neck upon the block. With outstretched hands, she murmured "Into thy hands, O Lord, I commend my spirit." The first blow of the axe did not sever her neck, the Queen's lips moved and she let out an audible groan before the axe came down again with a sickening thud. The task had to be completed with a sawing action before the head was completely severed, her lips were still seen to move for some time afterwards.

The eye witness account of Pierre de Bourdeille, which was published in 1665, describes the scene at Mary's execution:-

"she summoned her women to help her remove her black veil, her head-dress, and other ornaments. When the executioner attempted to do this, she cried out: 'Nay, my good man, touch me not!' But she could not prevent him from touching her, for when her dress was lowered as far as her waist; the scoundrel caught her roughly by the arm and pulled off her doublet. Her skirt was cut so low that her neck and throat, whiter than alabaster, were revealed. She concealed these as well as she could, saying that she was not used to disrobing in public, especially before so large an assemblage. There were about four or five hundred people present.

The executioner fell to his knees before her and implored her forgiveness. The Queen told him that she willingly forgave him and all who were responsible for her death, as freely as she hoped her sins would be forgiven by God. Turning to the woman to whom she, had given her handkerchief, she asked for it.

She wore a golden crucifix, made out of the wood of the true cross, with a picture of Our Lord on it. She was about to give this to one of her women, but the executioner forbade it, even though Her Majesty had promised that the woman would give him thrice its value in money. After kissing her women once more, she bade them go, with her blessing, as she made the sign of the cross over them. One of them was unable to keep from crying so that the Queen had to impose silence upon her by saying she had promised that nothing of the kind would interfere with the business in hand. They were to stand back quietly, pray to God for her soul, and bear truthful testimony that she had died in the bosom of the Holy Catholic religion.

One of the women then tied the handkerchief over her eyes. The Queen quickly, and with great courage, knelt dawn, showing no signs of faltering. So great was her bravery that all present were moved, and there were few among them that could refrain from tears. In their hearts, they condemned themselves for the injustice that was being done.

The executioner, or rather the minister of Satan, strove to kill not only her body but also her soul and kept interrupting her prayers. The Queen repeated in Latin the Psalm beginning In te, Domine, speravi; nan confundar in aeternum. When she was through she laid her head on the block, and as she repeated the prayer, the executioner struck her a great blow upon the neck, which was not, however, entirely severed. Then he struck twice more since it was obvious that he wished to make the victim's martyrdom all the more severe. It was not so much the suffering, but the cause, that made the martyr.

Memorial to Mary, Queen of Scots at Fotheringhay Castle

The executioner then picked up the severed head and, showing it to those present, cried out: 'God save Queen Elizabeth! May all the enemies of the true Evangel thus perish!'

Saying this, he stripped off the dead Queen's head-dress, in order to show her hair, which was now white, and which she had been afraid to show to everyone when she was still alive, or to have properly dressed, as she did when her hair was fair and light. It was not old age that had turned it white, for she was only thirty-five when this took place, and scarcely forty when she met her death, but the troubles, misfortunes, and sorrows which she had suffered, especially in her prison."

In a scene which evoked pathos even from her enemies, Mary's Skye Terrier, which had accompanied her into the hall concealed under her skirts, whimpering, splattered in her blood, it lay between the Queen's body and her decapitated head. It was dragged away and washed but pining and refusing to eat, the dog did not long survive the trauma.

Mary's body was encased in a casket of lead and buried at Peterborough Cathedral. The Queen's mercenary son, James VI, after registering protests solely for the sake of his reputation, accepted a pension from Elizabeth and lead her to understand that the sad scene played out at Fotheringay need not permanently affect relations between their two countries.

When James VI succeeded to the English throne in 1603, he became the first monarch of Great Britain. By way of reparation for his earlier treatment of her, he had his mother's body translated to the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey, the mausoleum of England's monarchs.

James provided a costly, magnificent and majestic white Marble monument to Mary's memory. He further ordered that the Castle at Fotheringay, the tragic scene of his mother's execution, be razed to the ground. Only a mound, where purple thistles are said to grow, remains today.

The Ancestry of Mary, Queen of Scots

Mary, Queen of Scots

Father: James V of Scotland

Paternal Grandfather: James IV of Scotland

Paternal Great-grandfather: James III of Scotland

Paternal Great-grandmother: Margaret of Denmark

Paternal Grandmother: Margaret Tudor

Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry VII of England

Paternal Great-grandmother: Elizabeth of York

Mother: Mary of Guise

Maternal Grandfather: Claude, Duke of Guise

Maternal Great-grandfather: René II, Duke of Lorraine

Maternal Great-grandmother: Philippa of Gelderland

Maternal Grandmother: Antoinette of Bourbon-Vendôme,

Maternal Great-grandfather: François, Count of Vendôme

Maternal Great-grandmother: Marie de Luxembourg

Mary's descendants-The House of Stuart

External LinksMary Queen of Scots and Tutbury Castle- article on Tutbury Castle and Mary's imprisonment there.

James V PreviousNext Mary of Guelders