King Henry V

Henry V revived his great-grandfather King Edward III's claim to the French throne and after negotiations with his French counterpart had broken down, led an English army into France in 1415, renewing what later came to be known as the Hundred Years War. Henry V 'let loose the dogs of war' and landing in France unopposed, he took the town of Harfleur, the siege took its toll on the English army, many died of disease, and a strong garrison had to be left behind to defend the town.

King Henry V

Henry then sent the Dauphin a message offering to settle their quarrel for the French throne by single combat, which was declined. Henry marched his army up to English Calais, a remnant of Edward III's conquests. Food was in short supply and a French prisoner informed the English that the ford over the Somme had been staked and guarded by a large French blockade. To add to the king's considerable troubles, dysentery, that scourge of medieval soldiers, was rife in his army. Henry's small army was now in a very precarious position, all bridges across the river had been smashed or heavily defended, but a way across was eventually discovered. The English army proceeded to march to Calais.

After the English army had passed beyond the town of Frévent, scouts reported the news that an immense French army blocked the road in the valley ahead. One of the scouts, a Welsh man-at-arms, named David Gambe, on being questioned by the king regarding the size of the French army, replied "There are enough to kill, enough to capture and enough to run away." Henry issued orders to encamp and prepare for battle the next day. Heavy rain fell that evening, Henry V made his way around his army offering words of encouragement, described eloquently by Shakespeare in his play.

On the 25th of October, 1415, the feast day of Saints Crispin and Crispinian, Henry led his small, exhausted English army against the might of the French chivalry at Agincourt. An estimated 5,000-6,000 English troops opposed a massive French army of 50,000-60,000. King Henry wore a polished and plumed helmet for the battle, surmounted by a gold crown, in which was mounted the Black Prince's ruby, presented to Edward, the Black Prince, in gratitude for his military assistance at the Battle of Navarette in 1367, by Pedro the Cruel of Castille. Henry's surcoat was emblazoned with the arms of England and France.

The English army took position across the road to Calais in three divisions of knights and men-at-arms, commanded by Lord Camoys on the right, the Duke of York in the centre and Sir Thomas Erpingham on the left. The Archers formed wedged divisions along the front. Further down the road, the French army was forming for battle. Charles d'Albret, the Constable of France headed the first French line. The Dukes of Bar and d'Alençon led the second and the Counts of Merle and Falconberg led the third.

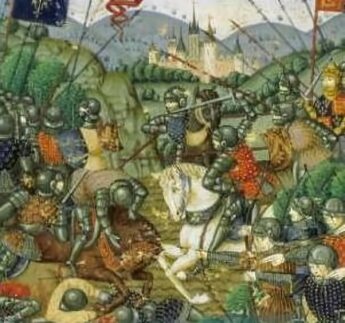

The Battle of Agincourt

Henry's army waited for the French to attack but they failed to do so, the English therefore advanced first, Henry's strategy was to fight where the field narrowed between two woods, to prevent the French from outflanking and surrounding him. It was said among the English archers that the French intended to cut off the first and second right-hand fingers of every captured archer to prevent him from again being able to use a bow. The English archers raised those two fingers to the advancing French as a gesture of defiance. English archers showered the French with repeated volleys of arrows.

The French chivalry then advanced through the muddy ground. The English archers planted six-foot stakes in the ground before them, the French chivalry were forced to retreat in front of their own men-at-arms, who were struggling across the muddy field. The French charge and retreat churned up the already muddy terrain between the French and the English.

Charles d'Albret, Constable of France led the attack of the dismounted French men-at-arms, which crossed the muddy field beneath a hail of arrows; some reached the front of the English line and pushed it back. When the English archers ran out of arrows they used hatchets, swords and mallets to attack the French men-at-arms. The exhausted French men-at-arms were described as being knocked to the ground by the English and then unable to get back up. As the mêlée developed, the French second line also joined the attack, but they too were swallowed up. The French men-at-arms were taken prisoner or killed in their thousands.

The massive French army was hemmed into a small space, having no room for manoeuvre, with disastrous results. Unable to rise in heavy armour, men who went down in the crush was suffocated in their armour. Humphrey, Duke of Gloucester, the king's brother fell from an injury in the groin and was surrounded by the French, Henry stood over his brother until he could be dragged to safety, the king received an axe blow to the head which knocked off a piece of the crown that formed part of his helmet.

The sword of Henry V

French casualties were enormous. The French knights tried to rally and attempt a further charge but realised further resistance was hopeless, within two hours of the battle commencing it was clear that the victory was going to go to the English. The French knight, Ysembart d'Azincourt, led a small force against the lightly protected English baggage train, seizing some of Henry's personal belongings, including a crown. Whether this was part of a deliberate French plan is unclear from the sources.

The Duke D’Alençon who was bringing up his division to the aid of the first line was overcome and about to surrender to Henry himself when he was struck dead. The Constable of France, Charles D’Albret, was slain along with many other prominent French nobles, including Edward, Duke of Bar, John, Duke of Alençon-Perche, Philip of Burgundy, Count of Nevers and Rethel and Antoine of Burgundy, Duke of Brabant. In all, French deaths amounted to some 8,000 men.

English losses are considered to have been in the hundreds, among the English dead was Henry's cousin, the obese Edward, Duke of York who was trampled into the mud and probably suffocated in his armour. Michael de la Pole, 3rd Earl of Suffolk and Dafydd Gam (Davy Gam) the Welsh hero who reputedly saved Henry's life, also, lay dead on the field. Henry knighted the Welsh man-at-arms David Gambe as he lay dying in the mud on the battlefield. During the battle the English knight, Sir Piers Legge is said to have laid on the ground wounded, while his mastiff dog fought off the French men-at-arms. Only when Sir Piers' squire arrived after the battle would the mastiff allow anyone near his master. Sir Piers died of his wounds, but the dog returned to England.

Henry had won a spectacular and glorious victory for England against all odds. Returning to England, via Calais in November, the Londoners gave a rapturous welcome to their hero King

The Battle of Otterburn PreviousNext The First Battle of St. Albans