Richard III

The Battle of Bosworth was fought on 22nd August 1485. One of the most significant battles ever to be fought on English soil sounded the death knell of the House of Plantagenet. The battle was fought between the armies of the last Yorkist king, Richard III and his Tudor challenger for the throne, Henry, Earl of Richmond, later to become King Henry VII, who represented the claims of the rival House of Lancaster.

Richard III

Henry Tudor landed at Milford Haven, in South Wales on the 7th August, accompanied by a few die-hard Lancastrian lords and about 2,000 French mercenaries. He marched through Wales, gathering reinforcements en route. The town of Shrewsbury opened its gates to him on 15 August and from there he advanced through Lichfield. He was expecting to be joined by the forces of his step-father, Lord Stanley, but received the disquieting news that Lord Stanley could not openly declare his support for the invaders, since Richard held his son, Lord Strange, hostage for his loyalty.

Henry Tudor

King Richard was stationed at Nottingham, and moved from there to to Leicester on 19 August. The two armies finally faced each other about two and a half miles south of Market Bosworth in Leicestershire were Richard probably camped on Ambion Hill.

Said to have spent an uneasy night before the battle, the king was disturbed by ghoulish nightmares and looked gaunt and pale on rising. Shakespeare depicts him as being haunted by the souls of his victims. As if to underline the fact that treachery had infiltrated his ranks, during the night, someone had pinned a rhyme to the Duke of Norfolk's tent:-

'Jack of Norfolk, be not so bold, For Dickon, thy master, is bought and sold.'

The battle Battle of Bosworth

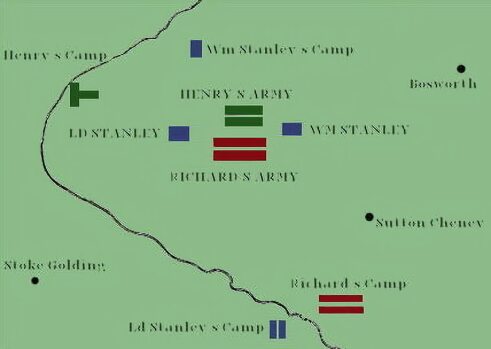

The Stanleys cautiously situated their troops to the sides of Richard and Henry Tudor's camps, openly declaring for, nor joining either. The King demanded Lord Stanley and his brother join him and was ignored. He reacted by angrily ordering Lord Strange to be beheaded, an action which was not carried out by a subordinate, no doubt fearing for his own position, should the battle not go well for the King. No priest could be found in the royal camp to say mass on the fateful morning of the battle.

Plan of the Battle of Bosworth

The Tudor army numbered around 5,000 men, whilst Richard commanded a slightly larger army of around 6,000. The Duke of Norfolk lead the vanguard of Richard's army, the King himself the centre, Northumberland had personally requested to be in the rear to watch the threatening Stanley's forces to the side. Though Richard was a seasoned campaigner, Henry had no experience in battle, Bosworth was his first field. Henry sent an appeal to the Stanleys to join him, but received the unerving response that the time was not yet ripe, leaving Henry, in the words of the chronicler Vergil "No little vexed".

The Battle was opened when Norfolk led the royal vanguard, according to the standard interpretation of the battle, down the slopes of Ambion Hill. The Earl of Oxford, commanding the Lancastrian troops, advanced his men to meet them. Henry remained at the rear, guarded by a troop of horse. The Lancastrians were met by a shower of arrows after which Norfolk ordered his men to charge. Oxford, an experienced general, skirted the hill with his men, unsure as yet of the intentions of the Stanleys. The Stanleys themselves, directed by the precarious position of Lord Strange, still made no move, but remained stationary, hovering in their menacing positions at both flanks of the battle, adding to the atmosphere of suspicion.

Oxford was heavily outnumbered and issued orders that his men were not to advance over ten feet from their standards. He had learned much from his disastrous experience at Barnet and feared he might lose command of his soldiers. He closed in, forming a wedge formation. Norfolk was killed in the fighting and his son the Earl of Surrey captured.

The eyes of the commanders remained on the looming and foreboding presence of the Stanleys, who still made no move. The air must have been thick with thoughts of treachery and self-preservation. Northumberland, not having gained the power in the north he had expected from Richard, also made no move, but continued to watch the Stanleys, desiring that whatever the outcome of the battle, he, Northumberland would be on the winning side. The Croyland Chronicler reported that-

In the place where the Earl of Northumberland stood with a fairly large and well-equipped force, there was no contest against the enemy and no blows were given or received in battle"

Had Northumberland's northern levies participated in the fighting, the outcome of the battle is likely to have been very different.

Richard was brought the ominous news of Norfolk's death and must have been in total despair and rage at the treachery surrounding him. Sighting Tudor's dragon standard, the King 'all inflamed with ire', after taking a drink from a spring later known as 'Dickon's Well', charged suicidally with his household straight for the person of Henry Tudor. It was both an impulsive and magnificently courageous gesture, if he could have just reached the Tudor, the issue would have been settled outright. Many of Henry's supporters were killed in the headlong charge, including his massive standard-bearer, Sir William Brandon. Watching and waiting for his moment, Stanley saw that now was the time to bring in his troops. Richard, although urged to flee, valiantly refused, insisting he would remain King of England or die in battle.

The Standard of Richard III

The shifting Stanleys moved in for the kill and Richard 'fighting manfully amid his enemies' was surrounded and fell, pierced by many wounds.

The contemporary chronicles state that he was urged to flee following the desertion of some of his followers and the collapse of his vanguard. Polydore Vergil, one of the early chroniclers of the battle, states that Richard replied that 'on that day he would make an end either of wars or of his life, such was the great boldness and great force of spirit in him'. Richard instead chose to lead a charge straight at Henry Tudor, killing several men and toppled Henry's standard, killing his standard-bearer William Brandon, and unhorsed the jousting champion Sir John Cheney, who stood in his way, thrusting him to the ground and forcing a path for himself through the press of steel.

Polydore Vergil recorded that ‘King Richard, alone, was killed fighting manfully in the thickest press of his enemies.’ According to the Burgundian chronicler Jean Molinet, Richard's horse became stuck in a marsh and then 'unhorsed and overpowered, the king was hacked to death by Welsh soldiers'. Molinet adds that a Welshman struck the death-blow with a halberd. The contemporary Welsh poet Guto'r Glyn also states that a Welshman, Rhys ap Thomas, or one of his men, delivered the fatal blow. Even afer Richard was dead, the of blows continued on his battered body continued, one source describes how Richard’s head was battered to the point that his basinet was driven into his head, ‘until his brains came out with blood’.

The chronicler Rous, not normally effusive in his remarks about Richard recorded of his last moments-

"If I may speak the truth to his honour, although small of body and weak in strength, he most valiantly defended himself as a noble knight to his last breath, often exclaiming as he was betrayed, and saying Treason! Treason! Treason!"

Many fled on the king's death, others surrendered. Legend states that Lord Stanley retrieved England's crown, which Richard had inadvisedly worn throughout the battle, from under a hawthorn bush and placed it on the head of Henry Tudor, which was met by the exhilarated shouts of his army "King Henry, God save King Henry!" The Tudor age had begun.

Aftermath

Following the battle, the Earl of Northumberland surrendered and was taken captive by Henry Tudor, he was however, soon released and confirmed in his titles and lands. He was murdered four years later during a riot. In an unpopular move, Henry later backdated the start of his reign to the day prior to the battle of Bosworth in order to attaint for treason all those who had fought for Richard III.

The new King of England, Henry VII then proceeded to Leicester. The body of King Richard III, which was recovered from the pile of corpses around Henry's banner, was treated with much indignity. Trussed naked over a horse and besmirched with mud, it was borne in parade to Leicester, a sad spectacle. It was exposed for two days at the Church of the Greyfriars at Leicester, where Richard III was later unceremoniously buried. Henry contributed £10 1 shilling toward the cost of a tombstone for his rival.

The father of the architect, Christopher Wren, is reported as having seen Richard's grave in the seventeenth century. The remains of Richard III were uncovered by an archaeological headed by the University of Leicester in collaboration with the Richard III Society and Leicester City Council, which began in August 2012. A formal announcement by Leicester University was made on the results of the tests on Monday, 4th February 2013, which confirmed the remains to be those of Richard. For further details see update- the remains of Richard III

White boar badge of Richard III, found on the battlefield

Recent reconsideration of the site of the battle has lead to the theory that it did not take place on the traditional site of the slopes of Ambion Hill but on but on a reedy moor, around half a mile to the south, near the village of Dadlington. For several years after the event the battle was actually referred to as the Battle of Redemore.

From August 2005 to July 2008 the Battlefields Trust undertook a new study of Bosworth battlefield, financed by the Heritage Lottery Fund. The project attempted to resolve many of the long standing questions surrounding the Battle of Bosworth and its actual location. The true site of the battle has now pinpointed to fields that straddle the Roman road known as the Fenn Lane, near Fenn lane farm, close to a proven medieval marsh, lying more than a mile to the south west of the traditional site near the Bosworth Visitor Centre.

Evidence such as cannon balls, the largest collection of that date in Europe was unearthed and pieces of armour including fragments of swords, bridle fittings and spurs have been used to confirm the location. A gilded silver badge in the shape of a boar, Richard's personal emblem, probably worn by one of his closest companions who rode with him on his final charge, was a significant find. There were also silver coins bearing the head Charles the Bold of Burgundy, a silver-gilt badge was found close to where it is believed the Duke of Norfolk was killed.

There is now a new trail from the visitor centre, which comprises of a 1.25 mile (2.2km) walk with audio and visual interpretation about the battle and surrounding area. Climbing Ambion Hill near the Battlefield Heritage Centre the trail also includes a walk-through sundial which features the thrones of Richard III, Henry Tudor and Lord Stanley. The panoramic view from the sundial provides the opportunity to see the actual battlefield site in the distance, the church of nearby Market Bosworth and other local landscape features.

The Battle of Tewkesbury PreviousNext The Battle of Stoke Field