1660-85. Early Life

The eldest surviving son of Charles I and Henrietta Maria of France, daughter of Henry IV of France, the future Charles II was born on 29th May 1630, at St. James Palace, London, the second child of the marriage, he replaced an elder brother, Charles James, who had died shortly after birth. Charles was a large, dark, but healthy baby.

Civil War broke out between his father and Parliament in 1642, causing Charles mother, Henrietta Maria and his younger siblings to be sent to the safety of her native France. Prince Charles and his younger brother, James, Duke of York, remained with their father during the early stages of the Civil War. He first saw action at the Battle of Edgehill, but following the defeat at Marston Moor in 1644, was sent to Bristol, where he was placed in command of the West Country.

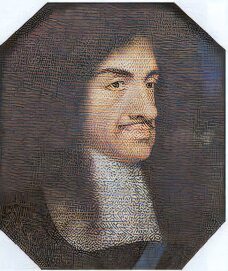

Charles II as Prince of Wales

Charles' appearance was anything but English, with his sensuous curling mouth, dark complexion, black hair and dark brown eyes, he much resembled his Italian maternal grandmother, Marie de Medici's side of the family. During his escape after the Battle of Worcester, he was referred to as 'a tall, black man' in parliamentary wanted posters. One of the nicknames he acquired was the black boy His height, at six feet two inches, probably inherited from his Danish paternal grandmother, Anne of Denmark also set him apart from his contemporaries in a time when the average Englishman was far smaller than today.

The Years of Exile

In 1646, as matters began to deteriorate for the Royalist cause and Parliament gained the upper hand, Charles was sent out of the country, where he joined his mother in France. When Charles I was on trial for life, the desperate Prince Charles sent Cromwell a carte blanche signed Charles P, thereby inviting Cromwell to name any terms for his father's life. Cromwell ignored the offer. He learned of his father's death when a fellow exile addressed him as "Your Majesty". Deeply distressed, Charles burst into tears and left the room.

In an attempt to regain the lost throne of the Stuarts, Charles sailed for Scotland to ally himself with the Covenanters against their mutual enemy, Oliver Cromwell. He found it a humiliating experience. Their dour form of Presbyterianism was forced on him and the young Charles, with characteristic cynicism, found he had "to repent me that I was ever born," On 3 September 1650, the Covenanters were defeated at the Battle of Dunbar by a much smaller force led by Oliver Cromwell. Charles was nevertheless crowned King of Scotland at Scone in January 1651.

With the Parliamentary forces threatening the royalist position in Scotland, the decision was reached to mount an attack on England. With many of the Scots refusing to take part, and with few English royalists joining the force as it moved south into England, Charles marched into England to confront Cromwell at the head of a Scottish army. Charles suffered defeat at the Battle of Worcester on 3rd September, 1651. The battle was short and culminated in a complete rout of the Royalist forces. The Duke of Hamilton had his head blown off, and Charles, having watched the progress of the battle from the Cathedral tower assumed command of his forces. He had two horses killed under him and half the Scots refused to charge, despite his admonitions " I command you - upon your honour and loyalty - charge!" they refused to advance on the enemy. Cromwell finally broke into Worcester and Charles was forced into flight. Two thousand Royalist troops lay dead, while 3,000 were taken, prisoner.

Charles II

Charles then spent six desperate weeks as a fugitive in hiding in England. He had his hair cut short to evade capture and donned leather breeches and a felt hat, immitating a country accent. After the Restoration the king loved to regale friends with accounts of his miraculous escape. He first took refuge at Boscobel House, near Worcester, where he narrowly escaped capture by famously hiding in an oak tree for the course of a day, consuming large quantities of beer, bread and cheese while praying he would avoid detection by the Roundhead troops which scoured the area.

He was assisted, among others, by the heroic Jane Lane, sister of Colonel Lane and posed as her manservant. Cromwell offered a reward of £1,000 for information which led to his capture. Charles also hid at Moseley Hall where he made the acquaintance of one Father Huddleston, a Roman Catholic priest. He was at one point told by a blacksmith attending to the horses that "if that rogue" (meaning Charles) " were taken, he deserves to be hanged more than all else the rest for bringing in the Scots." He boarded a ship to the continent at Shoreham, the captain, Nicholas Tattershall, was unaware of the identity of his illustrious passenger, having been informed he was a merchant escaping debts.

The next nine years of Charles' life were spent as a nomadic, aimless and at times penniless exile in Europe, his experiences aged him prematurely and made him ever more cynical and watchful. On 3rd September 1658, Cromwell died. His son, Richard Cromwell, to whom he had bequeathed the Protectorate, had no aptitude for government. Accordingly, General Monck laid proposals before Parliament for the restoration of the monarchy.

The Restoration of the Monarchy

Advised by his father's minister Edward Hyde, (later created Earl of Clarendon), Charles issued the Declaration of Breda promising to uphold the Anglican church, pardon his enemies and submit difficult matters to the direction of Parliament. This satisfied all but a hardcore element in England and he was invited to return as King.

Arriving at Dover on 23 May 1660, King Charles II entered London on 29th May, his thirtieth birthday, to a resounding welcome by around fifty thousand people. Bonfires flared, trumpets blared and flags were waved, as he set foot on the shore, he knelt and gave thanks to God. He spent the weekend at Canterbury before proceeding to London. General Monck presented him with a list of forty people he wished to see elected on the Privy Council, for which Charles thanked him. On entering London, he rode past Whitehall, the site of his father's execution. With typical cynicism, he later humorously remarked that it was undoubtedly his own fault that he had been away so long, as he had met with no one " who did not protest that he had ever wished for my return".

Catherine of Braganza

Charles' coronation took place at the traditional venue of Westminster Abbey on 23rd April, 1661. As the crown jewels of England had been melted down by Cromwell at the establishment of the protectorate, a new set had to be made for the occasion. Charles made it clear he was not about to repeat the mistakes of his father's reign. The Act of Indemnity and Oblivion forgave his enemies and despite the urgings of his mother, only the regicides, those who had signed his father's death warrant, were called to account, of which ten were sentenced to death. On 30th January, 1661, the twelfth anniversary of the execution of Charles I, the body of Oliver Cromwell and others of the regicides was exhumed from Westminster Abbey and posthumously executed. Cromwell's corpse was hanged in chains at Tyburn. The body was eventually thrown into a pit, while his severed head was exhibited on a pole outside Westminster Abbey until 1685.

Charles himself witnessed some of the executions of the regicides, as it was expected that he should, he was, however, moved and on a scribbled note to Clarendon during a meeting of the Privy Council he wrote 'I must confess that I am weary of hanging except on new offences....Let it sleep'.

Charles had a great interest in science, liked to conduct experiments in his laboratory and adored the theatre. 1662 saw the founding of the Royal Society, Charles was its official founder and John Evelyn and Robert Boyle were among its first members. The great scientist, Sir Isaac Newton lived in his reign, as did Hooke, inventor of the microscope, the famous architect, Sir Christopher Wren, the diarist Samuel Pepys and the poet Dryden.

The new King married Catherine of Braganza, the daughter of John IV, King of Portugal and Louise of Guzman on 21st May 1662 at Portsmouth first secretly according to Roman Catholic rites at Catherine's request and again publicly by the Bishop of London. She brought Bombay and Tangier into his possession as part of her dowry. The new Queen, although not beautiful, was good-natured and obliging, in a letter to Clarendon, Charles professed himself well pleased:-

'I can now only give you an account of what I have seen a-bed, which, in short, is, her face is not so exact as to be called a beauty, although her eyes are excellent good, and not anything in her face that in the least degree can shock one. On the contrary, she has as much agreeableness in her looks altogether as ever I saw; and if I have any skill in physiognomy, which I think I have, she must be as good a woman as ever was born. Her conversation, as much as I can percieve, is very good, for she has wit enough and a most agreeable voice. You would much wonder to see how well we are aquainted already. In a word, I think myself very happy; but am confident our two humours will agree very well together.'

The King's Mistresses

The Merry Monarch as he was later to become known, is famous for his many mistresses. While in exile, Lucy Walters had borne him a son, James, who was to become Charles' favourite son and whom he later created Duke of Monmouth. At the time of the Restoration, his reigning mistress was the temperamental Barbara Palmer, daughter of Viscount Grandison, cousin of George Villiers, Duke of Buckingham, and wife of the long-suffering Roger Palmer, she was a woman of voracious sexual appetites, who also bore him several children. She possessed a foul temper and used her considerable influence with the King to meddle in state affairs. Charles eventually tired of Barbara.

The best-remembered of all Charles' mistresses was perhaps Nell Gwynn the pretty cockney actress, once an orange seller in the theatres who was born in a London alley in 1650, her mother was known to have kept a brothel at Covent Garden. A true child of the London streets, Nell's ready wit amused the king. At the height of the Exclusion Crisis, when the religious feeling was at boiling point, Nell's coach was attacked by an angry mob who mistook her for the king's Catholic French mistress, Louise De Kerouaille. "Pray good people be civil" she cried, sticking her head out of the window, "I am the Protestant whore!" Although he had numerous children by his mistresses, the Queen, to her great sadness, remained barren. Catherine, after initial friction, came to accept the mistresses and she and Charles grew to be very fond of each other.

Barbara Villiers

Charles popularity with the people survived England's disastrous war with the Dutch, who in 1667 sailed up the River Thames into the Medway to sabotage the English fleet. The last great outbreak of the Bubonic Plague struck London in 1665, claiming thousands of lives during its inexorable march through the capital. It was perceived in some quarters as divine retribution for the licentiousness of the King and his court.

Louise De Kerouaille

The Great Fire of London

It must have appeared to be the judgement of God, when the further disaster of the Great Fire of London followed, the fire started in a bakery in Pudding Lane. Within hours, the flames had spread along the entire street. Fanned by strong winds, it blazed out of control for four days and three nights.

The King and his brother James, Duke of York, went out into the streets and did all they could to help fight the fire. In an attempt to contain it, buildings in the path of the flames were either pulled down or blown up, the King himself helped with the demolition work. A new London emerged from its ashes and Sir Christopher Wren was commissioned to redesign the ruined St. Paul's Cathedral.

Secret Treaty with Louis XIV

After a visit in 1670 from his much loved youngest sister Henriette, or 'Minette', as Charles fondly called her, the King signed a secret treaty with his cousin Louis XIV of France. Minette had been sent as envoy as she was now the wife of the French King's effeminate brother Phillipe, Duke of Orleans and lived at the French court. By the terms of the treaty, Charles was to convert to Catholicism when the time was ripe in return for a lucrative French pension. When Minette died shortly after her return to France, Charles was distraught. Rumours abounded that Minette had been poisoned by her foppish and homo-sexual husband.

The Popish Plot

The conversion to Catholicism of Charles' brother and heir, James, Duke of York, was to cause him a multitude of problems. Influenced in his decision by his wife, Anne Hyde, who had previously converted to Catholicism, James, " Dismal Jimmy" as Nell Gwynne was known to mockingly refer to him, was an ardent and passionate Catholic but his two daughters, Mary and Anne, heirs to the throne, were brought up in the Church of England, on the King's insistence. The elder of the sisters, Mary, was married to William of Orange as part of a political alliance with the Dutch.

Amidst an atmosphere of mounting hostility toward Catholics, Titus Oates invented the Popish Plot, a so-called attempt to kill the King, which he reported to the government. Lead on by the hysteria which surrounded the matter, Parliament impeached the Earl of Danby and sent him to the Tower when some of the secret negotiations with Louis XIV were leaked.

The Catholic James, Duke of York was Oates actual target, and the affair heralded the development of the Exclusion Crisis. Two factions formed, one supporting James and the other Charles illegitimate, but Protestant, eldest son the Duke of Monmouth. Eventually, Charles's wishes for the legitimate succession of his brother were respected. After it was discovered that the unprincipled Monmouth was involved in the Rye House Plot to assassinate both his father and his uncle James, the horrified King exiled him for life. Charles had forgiven his wayward favourite son much but they were never to meet again.

The Death of Charles II

On the morning of 1st February 1685, Charles arose feeling unwell and later suffered a seizure while being shaved, which resulted in the loss of the power of speech. A recovery appears to have been made and there was general rejoicing, but his condition began to deteriorate again and it was soon became apparent to all present that the King was dying.

Helped on his way, without doubt, by the frantic efforts of his doctors, he was purged, frequently bled and blistered, and red hot irons were applied to his shaven head. There are many theories as to what Charles II died of, but the most probable of these is uremia, a syndrome caused by dysfunction of the kidneys. The symptoms of the illness include nausea, vomiting, headache, dimness of vision, convulsions and finally coma.

At the last, at the prompting of the Duke of York, he was received into the Catholic Church. Father Huddlestone, a priest who had saved his life after the Battle of Worcester, was secretly ushered into the King's bed-chamber by the Duke. The King, with his mistresses and children around him, blessed them all and commended them into the care of James, adding with characteristic kindness "and let not poor Nelly starve".

At 6 o'clock on the morning of 6 February 1685, as the angel of death crouched over St James' Palace with suspended sword, Charles asked that the curtains be drawn, so that he could see the dawn over the River Thames for the last time. Soon after he lost the power of speech, and drifted into a coma, dying at noon.

Charles had been the most popular of the Stuarts and was sincerely mourned by his people. The Marquess of Halifax wrote of him

' The truth is, the calling of a King, with all its glittering, hath such a weight upon it, that they may rather expect to be lamented than envied. Let his royal ashes then lie soft upon him. If all who are akin to his vices should mourn for him, never Prince would go better attended to his grave.'

After lying in state in the Painted Chamber at Whitehall, the funeral of Charles II took place on 14th February, he was buried in a vault in the Henry VII Chapel at Westminster Abbey. He was succeeded by his brother as James II.

Queen Catherine survived her husband for many years, she spent much time at a convent at Hammersmith and later moved to Somerset House. For the sake of her late husband, she attempted to intercede with James II for the life of her errant stepson, the Duke of Monmouth. She returned to Portugal in 1692, where she spent her last years as Regent of the country during the incapacity of her brother, King Pedro, during which she was held with much esteem. Catherine finally died in 1705.

The International Ancestry of Charles II

Charles II

Father: Charles I of England and Scotland

Paternal Grandfather: James I of England and Scotland

Paternal Great-grandfather: Henry Stuart, Lord Darnley

Paternal Great-grandmother: Mary, Queen of Scots

Paternal Grandmother: Anne of Denmark

Paternal Great-grandfather: Frederick II of Denmark

Paternal Great-grandmother: Sophie of Mecklenburg-Güstrow

Mother: Henrietta Maria of France

Maternal Grandfather: Henry IV of France

Maternal Great-grandfather: Antoine de Bourbon, duc de Vendôme

Maternal Great-grandmother: Jeanne III of Navarre

Maternal Grandmother: Marie de' Medici

Maternal Great-grandfather: Francesco I , Grand Duke of Tuscany

Maternal Great-grandmother: Joanna of Austria

THE ILLEGITIMATE CHILDREN OF CHARLES II

See also;-

The Battle of Worcester and the