Basil Brown

In 1938, not long before the outbreak of the Second World War, archaeologist Basil Brown excavated an area of eighteen low mounds in the grounds of a country house at Sutton Hoo, along the banks of the River Deben near Woodbridge, in south-east Suffolk. He unearthed one of the most spectacular archaeological discoveries ever made.

Initial investigations of the Mounds numbered 3, 2 and 4 revealed that they had all been robbed in antiquity, though a few remaining fragments were indicative of high-status Anglo-Saxon burials.

Inside Mound 3 the ashes of a man and his horse were discovered, placed on a trough of wood. A Frankish axe and imported objects originating from the area of the eastern Mediterranean were also unearthed. Mound 4 was found to contain the cremated remains of a man and a woman, accompanied by those of a horse.

Anglo-Saxon helmet

In the spring and summer of 1939 Brown turned his attention to the largest mound, known as Mound 1. The mound was excavated to reveal the ghost of a vast thirty-metre long oak ship, the largest Anglo-Saxon ship ever to have been discovered. Although none of the original timber had survived, the clear imprint of the wooden planks of its hull and the ribs that held them together still remained as compacted sand. The ritual of boat-burial is a distinctly Anglo-Scandinavian tradition. The ship was found to have been dragged up from the nearby River Deben.

At the centre of the ship was the remains of a burial chamber, which was around the size of a small room. This structure was constructed of beams of oak measuring five inches square which had a gabled roof. The rotting of the wooden beams led to the eventual collapse of the structure when the tons of soil of the mound fell in, burying its contents for centuries.

Within the burial chamber, Brown found an amazing hoard of armour and weapons all dating from the seventh century, a sword of state, a sword harness and belt, spears and a wand with a small mount depicting a wolf god.

There were also coins, gold and garnet fittings, a lyre, silver vessels and drinking horns, produced from the horns of aurochs, a large type of ox which have been extinct since early medieval times, as well as silver mounted cups.

There were decorative shoulder-clasps made up of two matching curved halves, with panels of interlocking stepped garnets and chequer millefiori insets, surrounded by interlaced ornament of animals. The half-round clasp ends contained intricate garnet-work of interlocking wild boars with filigree surrounds.

Clothes, ranging from fine linen overshirts to shaggy woollen cloaks, leather shoes and caps trimmed with fur, were found at the east end of the burial chamber, these included an extremely rare long coat of ring-mail.

Fortunately, grave robbers never discovered the tomb, the hoard is the greatest 'treasure' yet unearthed in Britain. The magnificent Sutton Hoo helmet, found on the head's left side, has become an iconic symbol of the Sutton Hoo burial.

The helmet, consisting of a crested iron cap with a full face mask, cheek guards and a neck guard at the rear, is decorated with figures of fighting men, boars heads, a serpents head and a flying dragon, survived only as a mass of some 500 small fragments and was only reconstructed after years of painstaking work in the British Museum Laboratory. The face mask, which could be described as a beadugrima or 'battle mask' is the most remarkable feature of the helmet, it has eye-sockets, eyebrows and a nose, which has two small holes to allow the wearer to breathe freely. The bronze eyebrows are inlaid with silver wire and garnets.

Saxon shield

Along the west wall of the burial chamber at the north-west corner stood a very large circular shield, which had a central boss mounted with garnets and plaques of interlaced animal ornament. The front of the shield had two large emblems with garnet settings, one in the form of a predatory bird and the other a flying dragon. The shield is similar to ones found in Sweden. The British Museum now houses a reconstruction of the the shield, which incorporates the original iron boss and the surviving fittings on a replica body measuring three feet in diameter and made of leather-covered lime wood.

Alongside the occupant of the chamber was placed his sword, which lay by his arm. Although the blade, which measured three feet, had rusted and was also broken by the fall of the burial chamber roof, the sword's hilt fittings, decorated in gold with garnets and blue glass and its belt mounts remained intact. The sword is sheathed in a wool-lined scabbard of wood, leather and textiles.

The burial also contained a leather purse with a jewelled lid of the highest quality workmanship, adorned with designs in gold and garnets. The leather purse itself had rotted away, but inside it had been placed thirty-seven gold Merovingian coins, three coin-sized blanks and two billets.

No trace of the body of the occupant of the burial chamber was found, at first, it was thought that either the body not to have survived as the soil was too acid, or the ship was a cenotaph (i.e. an empty tomb). Analysis of soil samples for residual phosphate, a chemical that remains when a body has decayed to nothing, strongly suggests a body had been placed in the ship burial.

Shoulder straps

The coins found in the purse were minted between the years 575 and 620 AD. If the burial took place not long after 620, the body was thought to have belonged to one of four East Anglian kings- ( i) Raedwald, a member of the Wuffingas dynasty and the greatest of the kings of East Anglia, a descendant of Wuffa, the first king of the East Angles, who died in 578 A.D. Raedwald reigned circa 616- 625, (2) Raedwald's son Eorpwald, who was murdered by a pagan noble soon after he was baptised as a Christian in around 627, ( iii) Raedwald's son or step-son St. Sigebert, or Ecric, who possibly remained a pagan and died circa 635.

The Wuffingas were traditionally pagan and claimed direct descent from the great god Woden himself. The kingdom was also created in a pagan style, in contrast with Kent or Northumbria, which developed within a Christian ideology.

Although his identity can never be proven, of these candidates the chief contender is Raedwald, a convert to Christianity who abandoned his faith.

From around 616, Raedwald was the most powerful of the English tribal kings, according to the Venerable Bede he was the fourth ruler to hold imperium over other southern Anglo-Saxon kingdoms, the Anglo-Saxon Chronicle, written centuries after his death, refers to him as bretwalda (an Anglo-Saxon term meaning ruler of Britain).

It has been suggested that the large 'sceptre' found in ship burial could have been a symbol of the office of bretwalda. Rendlesham, once the capital and residence of the East Anglian kings, stands only 4 miles (6.4 km) from Sutton Hoo. It is likely that the name Rendlesham derives from the Anglo Saxon words for 'the home of the shield'.

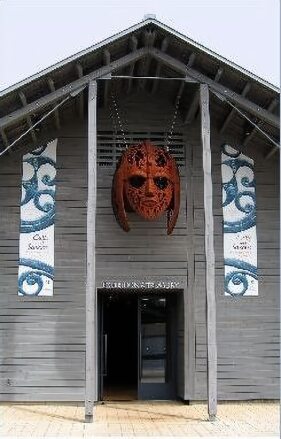

The Sutton Hoo Ship burial exhibition

The objects which were buried with the king were selected to reflect his royal rank and equip him with all the artefacts he might require in the afterlife.

The ship-burial has prompted comparisons with the world described in the epic anglo-Saxon poem Beowulf which is set in southern Sweden. Close archaeological parallels to the Sutton Hoo ship-burial are found in that area, particularly at Vendel. It has been suggested that the connection could imply that the Wuffing dynasty of East Anglia came from that part of Scandinavia.

Further burials and cremations were later unearthed at the Sutton Hoo site. Cremations in bronze bowls were found in Mounds 5,6 and 7, Mound 7 additionally contained gaming pieces and an iron-bound bucket, a sword-belt fitting and a drinking vessel, together with the remains of several animals that appeared to have been burnt along with the deceased on a funeral pyre. Mound 6 also contained cremated animals, gaming pieces, a sword-belt fitting, and a comb. In Mound 5 there were gaming pieces, a small pair of shears, a cup, and an ivory box. The Mound 18 although badly damaged, contained similar items.

Three burials were uncovered on an area of level ground between the mounds. One small mound was found to contain the remains of a child, along with a buckle and a very small spear. The most impressive of the burials without a chamber was that in Mound 17, where a man was buried with his horse, which would have been sacrificed for the funeral. The cemetery also contained several burials of individuals who had died violently, in some instances by hanging or beheading.

Subsequent archaeological excavations, particularly in the late 1960s and late 1980s, have investigated the wider site and many other individual burials.

Reconstruction of a Saxon burial

The Sutton Hoo ship-burial treasure was presented to the nation by Mrs Edith Pretty, who then owned the land which the mounds occupied.

The main items from the burial are now on permanent display at the British Museum. The Ipswich museum holds the original finds excavated in 1938 from Mounds 2, 3 and 4, and replicas of the most important items from Mound 1.

Sutton Hoo site, including Sutton Hoo House, was presented to the National Trust in the 1990s. At Sutton Hoo's visitor centre and Exhibition Hall, which opened in March 2002, finds from the equestrian grave and a recreation of the burial chamber and its contents may all be viewed. The Visitor Centre, constructed in 2001 to a design by the Architects van Heyningen and Haward, with an exhibition hall, visitor facilities makes the site and its finds more accessible to the public.

Another burial ground at Sutton Hoo was discovered and partly investigated in 2000, situated on a hill near the Exhibition Hall, located around 500 metres upstream from the first. This ground also contained burials under mounds, which lay undiscovered because they had long been flattened by agricultural activity in the area. Attention was first attracted to the area by the discovery of part of a sixth-century bronze vessel, of eastern Mediterranean origin, known as the 'Bromewell bucket' it decorated with a frieze of Syrian- or Nubian-style, which depicts naked warriors in combat with lions, and had a Greek inscription, it is now on display in the Exhibition Hall.

The Anglo-Saxon Tribal Kingdoms PreviousNext Beowulf