England's most enduring folk hero

The subject of ballads, books and films, Robin Hood has proven to be one of England's most enduring folk heroes. The often told legend of Robin Hood relates that in the days of King Richard the Lionheart, Robin of Loxley, a yeoman of Nottinghamshire, who, being driven to outlawry during the misrule of Richard's brother John, took to the greenwood of Sherwood Forest, from where he stole from rich travellers and distributed his takings among the poor.

Sherwood Forest

Robin gained followers, his band of "merry men", including Friar Tuck, Maid Marian, Little John and Will Scarlet. Despite the best efforts of the evil Sherrif of Nottingham he evaded capture until the return of King Richard from the Crusades brought about a full pardon and the restoration of Robin's estates. In other versions of the legend Robin died at the hands of his cousin, the abbess of Kirklees Priory.

Two other outlaws who operated at this time, Fulk fitzWarin and Eustace the Monk, were historical figures whose lives can be identified, Robin Hood himself presents more of a problem and the lines between fact and fiction, have become irrevocably blurred in the proceeding 800 years.

Robin Hood Statue, Nottingham

Documentary proof survives in the Court records of the York Assizes of 25th July 1225, which refer to a "Robert Hod". Penalties were recorded in the Michaelmas roll of the Exchequer, they included 32s. 6d. for the chattels of one Robert Hod, fugitive. In the following year the assizes referred to him again as "Robinhud", a bounty was placed on his head of 32 shillings and 6 pence.

By the year 1300 at least 8 people were called Robin Hood and at least 5 of which were fugitives from the law. In 1266 the Sherrif of Nottingham, William de Grey, was in conflict with outlaws in Sherwood Forest. It appears most likely that several different outlaws built upon the reputation of a fugitive in the forest, and over time, the legend was born, as early as the thirteenth century, Robin Hood had become a common epithet for criminals.

Another possible candidate for the real Robin Hood is Robert de Kyme. The Saxon de Kyme was outlawed in 1226 for robbing the King and disturbing the peace. De Kyme is said to have held lands that had been taken by the Earl of Huntington and retreated to the forest to plot his revenge.

The King's Remembrancer's Memoranda Roll of Easter 1262 records the pardoning of the prior of Sandleford for seizing without warrant the chattels of one William Robehod, a fugitive. The roll of the Justices in Eyre in Berkshire in 1261, in which a criminal gang is outlawed, including William son of Robert le Fevere, whose chattels were seized, apparently without warrant, by the prior of Sandleford. William son of Robert and William Robehod were the same man, it seems the clerk during his transcription had changed the name. Clearly, the clerk was aware of the legend and equated the name of Robin Hood with outlawry.

Sherwood Forest became a royal hunting forest after the Norman conquest of 1066, the Domesday Book in 1086 recorded that Sherwood Forest covered most of Nottinghamshire above the River Trent and was popular with many of the Plantagenet kings, particularly King John and Edward I. The ruins of King John's hunting lodge is still visible near the village of Kings Clipstone in Nottinghamshire.

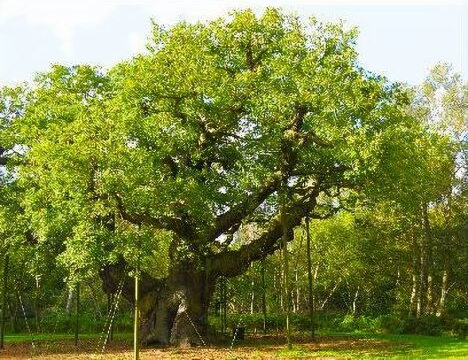

Medieval Sherwood was not a continuous swathe of dense virgin forest, it consisted of birch and oak woodland, interspersed with large areas of open heath and rough grassland. Sherwood also contained three Royal deer parks, near Nottingham Castle, Bestwood and Pittance Park. An ancient oak tree known as the Major Oak estimated to be about 800-1000 years old and with a girth of 35 feet, stands near the village of Edwinstowe in the heart of the forest. According to local folklore, it was Robin Hood's principal shelter, where he and his merry men slept.

the Major Oak, Edwinstowe

The first literary reference to Robin Hood comes from a passing reference in Piers Plowman, written down around 1377, and the main body of tales date from the fifteenth century. These are found in the tales of Robin Hood and the Monk (c.1450); The Lyttle Geste of Robyn Hode (written down c.1492-1510, but probably composed c.1400); and the C17th Percy Folio, which contains three C15th stories, Robin Hood his Death, Robin Hood and Guy of Gisborne and Robin Hood and the Curtal Friar.

These literary references contain no reference that places Robin Hood in the reign of King John, the only king mentioned in them is Edward II, probably refering to a visit by Edward to Nottingham in 1324.

In 1850, a historical document was uncovered which related the deeds of a forester, Robert Hood, who was born at Loxley who committed a series of minor offences, one of which was petty theft. According to recorded accounts, Robert may have become an outlaw due to his support for Thomas, Earl of Lancaster in his rebellion against King Edward II.

Maid Marian is a comparatively late addition to the legend, the legend of Robin and Marian originated in thirteenth-century France and Marion was later imported into the English legends in the fifteenth century. Other members of the band of merry men, also appear to have been embroidered into the tale at a later date. Only Little John and Will Scathlock, which evolved into Scarlet, feature in the original story. The first appearance of Will Scarlet was in one of the oldest surviving Robin Hood ballads, A Gest of Robyn Hode. In a churchyard in the village of Blidworth, which is situated at what was once the heart of Sherwood Forest, stands an oddly shaped stone, reputed to mark the grave of Will Scarlet. Legend states he was killed by one of the Sheriff's men and afterwards avenged by Little John. The stone is the apex stone from the old church tower, however, a Sherwood Forester is buried within the church itself who often found himself on the wrong side of the law and was eventually killed.

Little John, another leading character of the early Robin Hood legends, was Robin Hood's lieutenant, his second-in-command. In popular folklore, John Little is described as a "giant of a man", which prompted Robin to reverse his first and last names to create the ironic nickname by which he has since been known. Little John appears in the earliest chronicle references to Robin Hood, by Andrew of Wyntoun in about 1420 and by Walter Bower in about 1440, the name "Little John" or "John Little" was not uncommon and appears in many records of the period. One "Littel John" was reported to be part of a group accused of illegally killing deer in Yorkshire in 1323.

The grave of Little John, Hathersage

A headstone in churchyard of the church of St. Michael's in the Derbyshire village of Hathersage is claimed to be that of Little John. The celebrated English antiquary, Elias Ashmole wrote in 1625 'Little John lyes buried in Hathersage Churchyard within three miles from Castleton, near High Peake, with one stone set up at his head and another at his feete, but a large distance between them.' A number of local landmarks are associated with Robin Hood, such as Robin Hood's Cross on Abney Moor, Robin Hood's Stoop on Offerton Moor, and Robin Hood's Cave, on Stanage Edge. In 1780 James Shuttleworth and his cousin Walter Stanhope claimed to have unearthed a thigh bone measuring 72.39 cm, which would have made Little John measure 8.08 feet in height, the bone has now been lost.

The nineteenth-century editor and antiquary Thomas Wright insisted that Robin Hood was a mythical character and that his name was a corruption of 'Robin of the Wood'. Wright believed that he belonged to the early mythology of the Teutonic peoples, but failed to prove his theory. Sir Sidney Lee argued that the name originally belonged to a forest-elf, and that 'in its origin the name was probably a variant of 'Hodekin', the title of a sprite or elf in Teutonic folklore.

The legend relates that realising he is dying, Robin decides to be bled by his cousin, the prioress of Kirklees, a woman "skilled in physic." Bleeding was a common medical procedure in medieval times. On the journey to the priory, they meet an old hag who curses Robin. On arrival, the prioress takes Robin into the gatehouse and sends Little John away. She then proceeded to bleed Robin accompanied by her lover, the priest Red Roger of Doncaster.

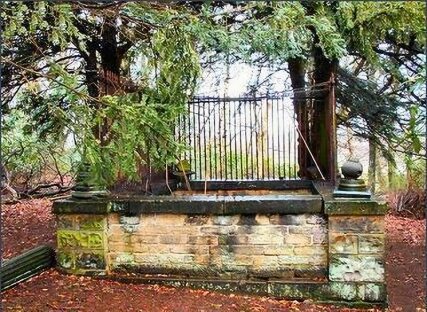

Robin Hood's Grave, Kirklees

In the grounds of Kirklees Priory, four miles north-east of Huddersfield in West Yorkshire stands a grave, dated to 1247, with a stone that marks it as the final resting place of "Robard Hude". According to legend, the mortally wounded Robin decided his own burial site by shooting an arrow from his death bed.

The legitimacy of the Kirklees site is open to question, and it has been dismissed by some authors as an eighteenth-century folly. The current enclosure was built in the 1700s, but references to the site of the grave dating back to the 1530s, hint at its greater antiquity. The antiquary John Leyland visited Kirklees in 1542 when he recorded "Resting under this monument lies buried Robin Hood that nobleman who was beyond the law."

In 1562, Richard Grafton visited Kirklees and stated-

"the sayd Robert Hood, beyng afterwardes troubled with sicknesse, came to a certein Nonry in Yorkshire called Bircklies, where desirying to be let blood, he was betrayed and bled to deth. After whose death the Prioresse of the same place caused him to be buried by the high way side, where he had used to rob and spoyle those that passed that way. And upon his grave the sayde Prioresse did lay a very fayre stone, wherin the names of Robert Hood, William of Goldesborough and others were graven. And the cause why she buryed him there was for that the common passengers and travailers knowyng and seeyng him there buryed, might more safely and without feare take their jorneys that way, which they durst not do in the life of the sayd outlawes. And at eyther end of the sayde Tombe was erected a crosse of stone, which is to be seene there at this present.'

The original grave slab which featured a large cross and the inscription, "Here lie Roberd Hude " has long since disappeared, it was recorded as having already been "broken and much defaced" in 1786. The present inscription in Victorian pseudo-gothic reads:-

'Here underneath dis laitl stean

Laz Robert Earl of Huntingtun

Ne'er arcir ver as hie sa geud

An pipl kauld im Robin Heud

Sick utlawz as him as iz men

Vil England nivr si agen.'

William Marshal PreviousNext Eleanor of Provence