The Proto-Celtic language

The Proto-Celtic language - the first Celtic language that arose from an Indo-European common ancestor, was once spoken all over the western part of Europe. The Gauls (of France) were the last known mainland Europeans to speak some form of Celtic.

Languages grouped as Insular Celtic, the Gaelic and Brythonic Celtic forms of Celtic, were spoken by the occupants of the British Isles. The oldest known Insular Celtic language is Old Irish or Goidelic, which eventually evolved into the Irish Gaelic, Scottish Gaelic, (Gàidhlig) and Manx (Gaelg) languages. Manx is closer to Scottish than Irish Gaelic. Brythonic Celtic was spoken in England, Wales and Lowland Scotland.

The P-Celtic language of the original Britons began to fragment over time due to dialect differences.The tribes of the north of England spoke a P Celtic now extinct language known as Cumbric, which was closely related to the Welsh (Cymraeg) and Cornish (Kernewek) languages. Breton (Brezhoneg), first attested in the eighth century is still spoken in Brittany, particularly in the western regions. Breton is not a form of Continental Celtic as was formerly thought, but is actually an insular Celtic language which is closely related to Cornish.

Proto-Celtic language

Welsh

Welsh, a language in revival, remains widely spoken in north Wales. Of all Celtic languages Cymraeg has the largest number of first language speakers. Old Welsh (Hen Gymraeg) was spoken from the ninth to the eleventh centuries. After the Anglo-Saxon colonisation of England, the Welsh were cut off from the Cumbric speakers of northern England, and the Britons of the extreme south-west, whose language would eventually evolve into Cornish, and with poor communications, their languages began to diverge.

Brythonic Celtic Language In common with English, Welsh has changed with the passing of the centuries. Middle Welsh (Cymraeg Canol) spoken from the twelfth to the fourteenth centuries, is the language of nearly all surviving early manuscripts of the Mabinogion. Middle Welsh is reasonably intelligible to a modern-day Welsh speaker. By the onset of the twentieth century, Welsh was dwindling as a spoken language at such a rate to be suggestive that it would be extinct within a few generations. The Welsh Language Act of 1993 placed the Welsh language on an equal footing with the English language in Wales with regard to the public sector.

Cumbric

The Cumbric language lingered on in the western borderlands between England and Scotland until as late as the tenth century. It was once widely spoken throughout an area between the river Mersey and the Forth-Clyde isthmus, particularly in Cumbria, a region once encompassing southern Scotland, and North England (Cumberland, Westmorland, parts of Northumberland, Lancashire and possibly North Yorkshire). The evidence for Cumbric is derived through secondary sources since no contemporary written records of the language survive.

The early poets Aneirin and Taliesin lived in Southern Scotland and composed their poems in Cumbric, but as the poems were passed down by oral tradition the versions which survived to the present are no longer in their Cumbric form but in early Welsh. Cumbric was eventually replaced by English and its Scottish variant - Lowland Scots.

Although now an extinct language, some farmers in Cumbria still count sheep using terms that derive from Cumbric - eg Yan, Tan, Tethera, Methera, Pimp compared to Old Welsh "Un, Dou, Tri, Petwar, Pimp". Evidence of the Cumbric language survives in the place-names of the far northwest of England and the South of Scotland, such as Lanark, deriving from the equivalent of Welsh llannerch 'a glade, clearing', Glasgow, from words equivalent to Welsh glas gau 'green hollow'. Place names such as Penrith and Blencathra are also Brythonic linguistic vestiges,

Penrith means 'chief ford' (Welsh pen 'head; chief' and rhyd 'ford'). Blencathra, a mountain in England's Lake District, means "Devil's Peak" in Old Cumbrian, it was so named because the Celts believed that the god of the underworld dwelt there. The place-names of Cumbria and Cumberland refer to the Brythonic people. "Cymri" or "Cumber" means comrades or brothers which the Welsh also referred to themselves as. The name of the Celtic kingdom of Rheged derives from the Brigantes tribe, who inhabited northern Britain, Brigant evolved into Breged, then Rheged.

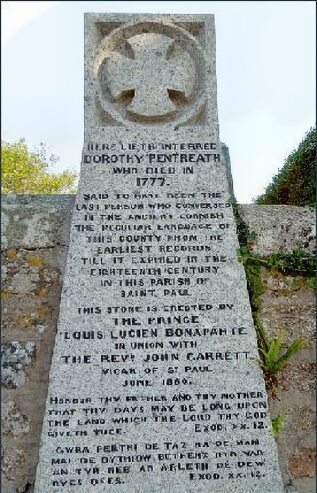

The grave of Dorothy Pentreath

Cornish

Brythonic Celtic also survived as Cornish, which was spoken in a small region of south-western Britain, Cornish started to diverge from Welsh towards the end of the seventh century and is closely related to Breton. The earliest known examples of written Cornish date from the end of the ninth century. J. Loth, in his 'Chresthomathie bretonne' (1890) states that Cornish and Breton speakers could have understood one another as late as 1600. The English Reformation hastened the decline of the Cornish language, by the late seventeenth century, the language remained spoken only in the western parts of Cornwall. The last monolingual Cornish speaker, Dorothy Pentreath of Mousehole (baptised 1692) who died in December 1777, she was said to have frequently cursed people in a long stream of fierce Cornish whenever she became angry. A memorial stone to Dolly Pentreath is set into the wall of Paul churchyard, near Mousehole in 1860 by Prince Louis Lucien Bonaparte, Napoleon's nephew.

As with many other "last native speakers", controversy exists over Dorothy Pentreath's status. After her death, the antiquary Daines Barrington received a letter, written in Cornish and accompanied by an English translation, from William Bodinar, a fisherman from Mousehole, claimed that he knew five people who could speak Cornish in Mousehole alone. Barrington also reports of John Nancarrow of Marazion, a native speaker of Cornish who survived into the 1790s. John Davey, a farmer and schoolteacher of Boswednack, Zennor, near the north coast of the Penwith, who died in 1891, also conversed in Cornish, a memorial stone at Zennor church was erected by the St Ives Old Cornwall Society in his memory. John Mann of Boswednack, Zennor, was the last known survivor of a number of traditional Cornish speakers of the nineteenth-century, he was said to have conversed in Cornish with other children and was still alive at the age of 80 in 1914.

Many Cornish place names survive, such as Tre as in Trebetherick and Trelissick and many more Cornish place names mean a homestead and its nearby buildings. The Cornish prefix Pol as found in Polperro, Poldhu, Polzeath, Polruan, means a pool and Pen as in Penzance, Pendennis, Penryn, Pentire, etc means an end of something, a headland or head. Some Cornish words still appear in the English spoken in Cornwall today. The language underwent a revival in the latter half of the twentieth century.

Pictish

The Pictish language was spoken in East Scotland before being replaced by Scottish Gaelic. Some argue that the Picts spoke an ancient language indigenous to the area, which predated the Celtic languages of the Britons, while others claim Pictish was a form of Celtic. No agreement has been reached on where exactly it fits within the Celtic family of languages. The writing system which the Picts used, Ogham, actually originated in Ireland. Some linguists believe that Pictish is closely related to Gaulish whilst others claim it is a Brythonic language closer to Welsh. It is possible that Pictish was related to the Brythonic languages but diverged from them early and still contained a higher influence from Continental Celtic languages.

Maiden Castle PreviousNext Lindow Man