Hill forts

Hillforts existed in Britain from the Bronze Age, but the majority of British hillforts date from the Iron Age, when they reached their heyday, between 700 BC and the Roman conquest of 43 AD. Varying from mere mounds to huge ramparts, these Dark Age fortresses dot the British landscape, vestiges of an age of warriors, sacrifice and ritual and murderous retribution. These large defensive enclosures protected by a series of steep ditches can usually be found occupying prominent hilltop positions. In times of attack, the local populace may have sought refuge within the hillforts.

Danebury Hill Fort

Iron Age HillfortsThere are over 2,000 Iron Age known hillforts in Britain, standing sentinel to a bygone age of tribal warfare, nearly 600 of them are situated in Wales. Danebury Hill Fort which lies around 12 miles from Winchester, is the most thoroughly investigated hillfort. Maiden Castle in Dorset is the largest, covering 45 acres with huge earth walls rising to around 6 metres, even by modern standards, Maiden Castle is a massive earthwork. In the Iron Age, Maiden Castle was occupied by the Durotriges tribe, who inhabited the areas of modern Dorset, south Wiltshire, south Somerset and Devon east of the River Axe.

Fin cop hillfort in Debyshrie

Liddington Castle

Liddington Castle in Wiltshire was one of the earliest hill forts in Britain, sometimes cited as the location of the fifth century Battle of Mount Badon, it is situated on a commanding high position close to The Ridgeway. The earthworks consist of an oval bank of timber and earth fronted by a ditch, with entrances on the east and west sides. A palisade of wooden posts may have lined the top of the bank.

Warfare between the Celtic tribes of Britain could be brutal, bloody and savage as an excavator of the Fin Cop hillfort near the village of Ashford-in-the-Water in Derbyshire found when they made a gruesome discovery. An Iron age mass grave at the site of the fort contained the unceremoniously buried remains of only women and children, nine skeletons of women, one of whom was pregnant, four babies, a toddler of around two years old and a single teenage male who was found in an in a crouched position. Women, babies and children had either been stabbed or strangled, stripped of possessions and thrown into the ditch that encircled the fort. There was a total absence of adult males, whom it is assumed were either killed in battle or pressed into military service or sold for slaves by their captors.

The skeletons were discovered in a section of a ditch around the fort. The fort's stone wall had been broken up and the rubble used to fill the 400-metre perimeter ditch, where the skeletons were found. Their attackers then toppled a thirteen-foot high limestone wall over their bodies, covering the mass grave with rocks and soil. Animal bones, also buried in the ditch, suggest the fort's inhabitants kept cattle, sheep and pigs.

excavations at Fin cop

A further skeleton dating to the same time period, which belonged to a child, was discovered in a cave below the site in 1911 and could be related to the same event. The archaeologists are puzzled by the apparent absence of adult males at Fin Cop. None of the victims displayed fatal trauma on their bones, and it seems most likely that the cause of death was soft tissue wounds. There were no personal possessions buried with them, suggesting the captors removed any valuables. Seven of the skeletons have been radiocarbon dated to between 410-40 BC.

Dr Clive Waddington, who directed the two-year dig for Archaeological Research Services, commented "In recent years there has become an almost accepted assumption that warfare in the British Iron Age is largely invisible. Hill forts have been seen as displays of power, prestige and status rather than places with a serious military purpose". He added "For the people living at Fin Cop the hurriedly constructed fort was evidently intended as a defensive work in response to a very real threat".

The grim discoveries at Fin Cop have reopened the debate on the purpose of hill forts. For the people living here, the hurriedly constructed fort was evidently intended as a defensive work in response to a very real threat. “The ditches and fort were never finished. They had started to make a second wall but that wasn’t completed. You can tell that it was a hasty thing – they were trying to rapidly build it and it was not done on time.” Significantly, Fin Cop was probably not the only settlement to have been destroyed by attackers. For just a few miles away, at Bakewell, another fortified settlement appears to have met a similar fate.

After the Roman conquest, the Romans occupied some of the hillforts, such as the military garrison at Hod Hill, and the temple at Brean Down, but others were destroyed and abandoned. Where Roman influence was less strong, such as in Ireland and northern Scotland, hill forts were still constructed and used for several more centuries.

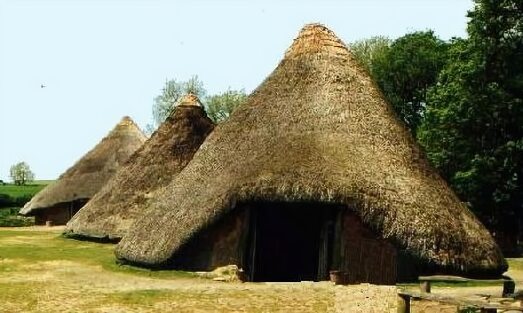

Castle Henllys hill fort

Cadbury Castle

Cadbury Castle in Somerset, thought by some to be the Camelot of Arthurinan legend is the largest amongst the forts reoccupied following the end of Roman rule, to defend against the onslaught of the Anglo-Saxons. Partially articulated remains of between 28 and 40 men, women and children at Cadbury Castle was thought to implicate the Cadbury population in a revolt in the 70s although this has subsequently been questioned. The Romano-British cemetery by Poundbury hillfort contains Christian burials of the fourth century.

The Wansdyke

The Wansdyke was a linear earthwork that connected to the existing hill fort at Maes Knoll, which defined the Celtic-Saxon border in southwest England during the period 577-652 AD. It consists of a ditch and embankment, with the ditching facing north. There are two main parts, an eastern dyke that runs between Savernake Forest and Morgan's Hill in Wiltshire, and a western dyke that runs from Monkton Combe to the ancient hill fort of Maes Knoll in Somerset.

Archaeologists have discovered evidence of a massacre involving hundreds at Ham Hill hillfort near Yeovil. Some of the bodies, which were predominantly women, were stripped of their flesh or chopped up. The remains unearthed have cut marks, often in multiple rows, and occurring at the ends of important joints. "It is as if they were trying to separate pieces of the body", according to Dr Marcus Brittain, the Cambridge archaeologist and head of the excavation. The remains are said to date from the 1st or 2nd century AD.

The massacre remains unexplained but occurred around the start of the Roman invasion of Britain. Evidence of Roman military equipment in the form of large ballista bolts has been found among the bodies. One theory in an attempt to explain the mystery is that the Romans executed people in keeping order between the Celtic tribes, but it's unlikely that they did the defleshing because the gruesome practice is rarely associated with them. Defleshing was linked to Iron Age Britons who often placed the skulls of their enemies on doorways.

The Celtic Tribes PreviousNext Maiden Castle